Why Panic Buttons are not the Solution

During my senior year of high school, there was a student who we were told had access to a gun and a plan to shoot up the school. My school went into lockdown and evacuated. Growing up just 30 minutes from Sandy Hook Elementary School, I remember the exact moment the shooting was announced over my middle school's PA system. It was surreal. Unfortunately, these experiences are all too common across the United States.

I started working in public safety in direct response to this proliferation of violence.

When I co-founded Prepared in 2018, there was a school shooting almost every other day. This problem — and public safety more broadly — was something my co-founders and I thought about regularly. We started off with a simple idea: build a panic button for schools. Our thinking was straightforward: if there had been a faster way to report an emergency, the response could have been quicker. And faster response times save lives.

It seemed like a no-brainer at the time, and the solution we built gained adoption quickly in schools across the US. Our app launched across New Haven public schools and a dozen other districts across the country, helping to protect over 100 schools — training and running drills regularly.

However, as I have worked in the space and evolved Prepared over the past several years, I have realized the problem is much more complicated. Panic buttons, while a well-meaning solution, don't address the deeper issues in public safety and emergency response. Prepared stopped offering its Panic Button solution back in 2022.

The Rise of Panic Buttons in Schools

The value proposition of the panic button is simple to explain: easy and fast reporting and response to emergencies within a school. The solution has become massively popular — backed by Alyssa's Law legislation influencing state legislatures to mandate buttons for schools with millions of dollars in funding and bipartisan support.

However, the school shooting problem may need more nuanced solutions than the state legislatures have currently implemented. Panic button solutions are now adopted in 40% of schools across the US — up from 27% in 2016 based on a study by Pew Research — but neither the frequency of school shootings nor the loss of life during these events has decreased since then based on research from Everytown.

The problems lie with both how these solutions affect those reporting the emergencies (within a school) and those responding to emergencies (911, EMS, Fire, PD).

Challenges of Adoption and Real-World Limitations

To get a panic button to work effectively in a school, you need four key elements:

- Broad adoption across the school staff

- Reports be trusted + actioned upon by all staff

- Regular training and drills

- Adoption by law enforcement

At Prepared, we experienced challenges at each level making it hard to justify that our solution was actually helping the schools make their students safer and not just confusing them.

For adoption by teachers and the staff, it was, frankly, like pulling teeth to get teachers to download, train on, and actually use the app the school mandated in different emergencies.

- Teachers didn't want to install a school-sanctioned app on their personal phones.

- Many of the staff members, especially part-time or contract workers, were not involved in the training and thus never downloaded the application.

- Much of the staff didn't want to have their phone on them during the school day.

- Turnover of staff made ensuring everyone was on the same page a logistical challenge.

This isn't a problem faced just by Prepared but seems quite common across other panic button solutions — adoption, broad buy-in, and usage are real challenges.

"The Little Rock, Ark., district previously attempted to use an app-based system, but less than 20 percent of staff downloaded the app" — Ron Self, Little Rock director of safety, security, and risk management (CNBC)

"In Florida, only about five people in any given school have the app on their phone" — Sheriff Bob Gualtieri, Pinellas County (AP News)

The challenges I've seen with panic buttons exacerbate the procedural breakdowns we see in mass shootings, and can arguably make the response process worse for those involved. By having low adoption on the school side, we are essentially designating multiple ways to report emergencies — resulting in unnecessary friction for both those at the emergency site and those trying to resolve the emergency (911, EMS, Fire, and PD).

The Problem of Dual Reporting

Here's a scenario: you're a teacher in a school. There's an active shooter, and you've trained on the panic button app, but it's been a while. Do you fumble with your phone, log into the app, and hope you can remember how to report the emergency? Or do you call 911, something you've been taught to do since childhood? Most people will choose the latter. But now, there are two reporting systems — the app and 911 — running in parallel.

"Teachers felt dialing 911 was more straightforward than accessing a mobile panic button app. Staff also shared concerns about privacy and reliability without Wi-Fi coverage" (ESchool)

This dual-reporting system creates confusion not just for the people in the emergency, but for 911 centers too. There's an inherent inefficiency when you have two systems trying to handle the same problem and neither is fully integrated.

This split in how emergencies are reported means that sometimes schools use the panic button, and sometimes they call 911. For the responding emergency services, this can create delays. If the 911 center is covering dozens of schools, but not all of them use the panic button, their response depends on the school's reporting process. If a system isn't drilled regularly, with ALL emergency personnel being involved in the drill, it's easy to forget how to use the system and revert to the way they respond to all other emergencies.

The panic button then introduces multiple new points of failure:

- Training on the panic button system isn't sufficient.

- Staff default to calling 911, creating split reporting channels.

- Panic button adoption isn't consistent across all schools.

- 911 response procedures vary based on how the emergency is reported.

What we need is a single, unified way to report emergencies that removes confusion for everyone.

Overloaded 911 Centers

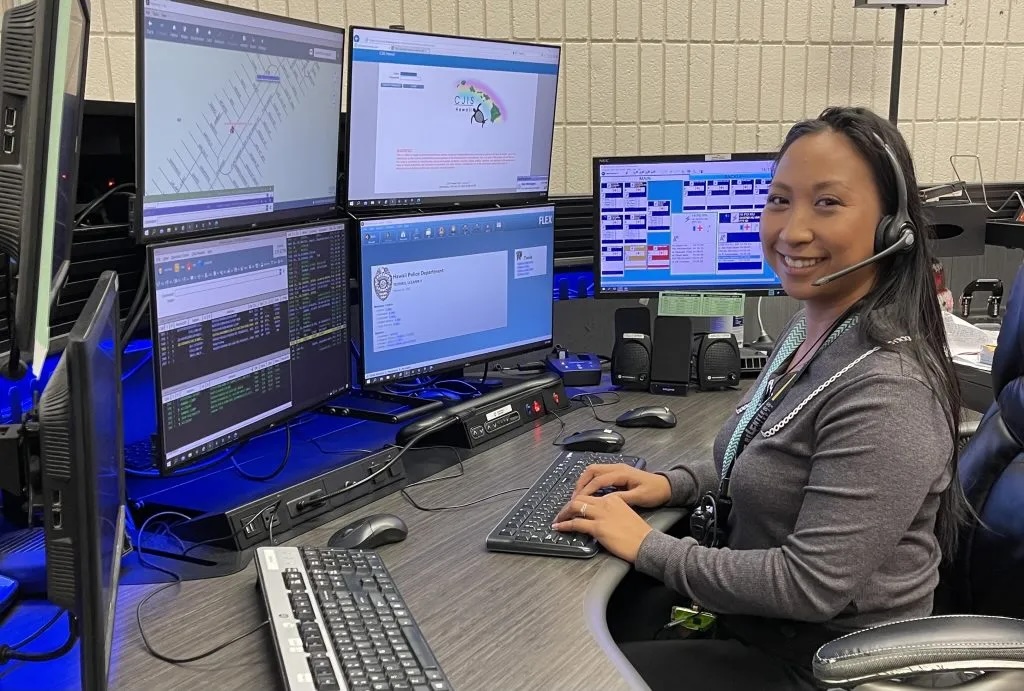

The reality is, 911 centers are already overwhelmed with different ways to get information about an emergency. A call comes into the 911 center, the operators have to fight against outdated technology, getting data from and reporting information to 20 different softwares — across 6-10 different monitors, 3 different computers, and 3 different mice.

They're already handling call systems, computer-aided dispatch (CAD) systems, location tracking, radio communications, and newer tech like Apple and Google location services. Adding yet another layer for school emergency alerts only increases their mental load.

When dispatchers are stretched too thin, things start to slip through the cracks. The stress of balancing so many systems with competing priorities leads to slower response times — which is exactly what panic buttons are supposed to prevent.

Now imagine a 911 center responsible for multiple schools in their jurisdiction, all using different panic button systems, with teachers that sometimes use the panic button and sometimes call 911. The dispatcher has to:

- Monitor alerts from each provider, none of whom have any incentive to make their system compatible with others.

- Respond to the hundreds of 911 calls that will follow the initial report

- Notify the school about that emergency

Once the 911 center gets the alert, they have to follow a unique protocol for that specific school, which complicates emergency response standardization across the city.

This variability isn't just an operational problem — it's a human one. The mental toll on dispatchers is already huge, and we shouldn't be adding more complexity to their jobs.

What a Better Solution Looks Like

Instead of adding more complexity to the system, we need to simplify it. What if, instead of having a separate panic button system, the only thing a teacher or student had to do was call 911 — something we've all been trained to do since childhood?

Let's walk through a typical emergency situation as it works today:

- [0:00] A high school student sees another student with a gun while outside the school.

- [0:10] The student dials 911.

- [0:15] The 911 operator answers the call.

- [0:35] The student reports that there is a student with a gun at X High School.

- [0:55] The 911 operator writes up the report and raises a hand for assistance.

- [2:30] The 911 operator contacts the school via the admin line to inform them of the emergency.

- [3:00] Someone answers the admin line and finds out about the emergency.

- [4:00] The school staff navigates to the PA system and announces the emergency to the entire school.

Now, here's what it could look like with an integrated and automated system:

- [0:00] A high school student spots a student with a gun while outside the school.

- [0:10] The student dials 911.

- [0:15] The 911 operator answers the call.

- [0:15] The 911 system instantly uses the phone's location (through services like ELS and EED) to automatically confirm that the caller is within the school's geofence.

- [0:35] The student says there is a student with a gun at X High School.

- [0:40] An automated workflow is triggered, notifying all relevant school emergency response teams (via mobile app, phone call, text message, or pager-style alert).

- [0:55] A summary of the 911 call is sent via SMS, phone, or the mobile app to all key personnel.

- [1:00] Another caller dials 911 and confirms the emergency.

- [1:10] The system automatically links the calls as related incidents, updating the school emergency response team with real-time information to help them make better-informed decisions.

- [1:30] The school uses the PA system to notify the entire building of the emergency and initiate the response procedure.

This approach ensures rapid, automatic compliance with emergency protocols while leveraging the existing legislative requirements for 911 calls. It works seamlessly, ensuring that anyone — regardless of their phone carrier or plan — can report an emergency. This system provides the same level of immediate alerting that a panic button would, but with the added benefit of 100% adoption (since everyone knows how to call 911). Best of all, it reduces the burden on 911 dispatchers by automating key steps, allowing them to handle the emergency more efficiently.

At Prepared, we're building exactly this kind of system — making it easier for emergency services to respond and closing gaps in public safety at scale. Automated workflows for school alerts are just one part of a broader solution that tackles general emergency response more effectively.

We Need More Innovation in Public Safety…

When we first built panic buttons at Prepared, we believed they were solving a critical issue. But over time, we realized the real problem wasn't how schools reported emergencies — it is the archaic tools that 911 centers and emergency responders use during these situations. Panic buttons, while well-meaning, add unnecessary complexity without addressing the root issue. They are a temporary, politicized fix for a larger, more pressing problem: outdated and overburdened 911 systems.

What we need is a fundamental shift in how we approach emergency response, focusing on integrating schools and 911 centers through modern technology. I am committed to solving the root problems in public safety through practical and technological solutions.

If we truly want our communities to be safer, we need to invest in fixing the core problems within emergency services instead of relying on quick fixes like panic buttons.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are my own and do not necessarily reflect the official stance or policies of Prepared. While I have drawn from my experiences working in public safety and emergency response, these opinions are personal and intended to spark conversation and reflection on how we can improve our approach to safety in schools and beyond.